Exploring the Four Types of Attribution: Understanding Internal and External Factors

Attribution, in psychology, is the way we explain why things happen—how we infer the causes of behaviors and outcomes. The core idea is straightforward: we look for causes and place them somewhere, often without realizing it, on dimensions like “inside me vs. outside me” and “fixed vs. changeable.” For formal grounding, see the American Psychological Association’s definition of attribution in the APA Dictionary of Psychology and its overview of attribution theory.

Why it matters: these explanations influence our emotions, expectations, and future actions. A setback blamed on an unchangeable trait can sap motivation; a setback tied to effort can galvanize improvement. Encyclopaedia Britannica’s overview of attribution dimensions describes how locus, stability, and controllability shape motivation.

Key takeaways

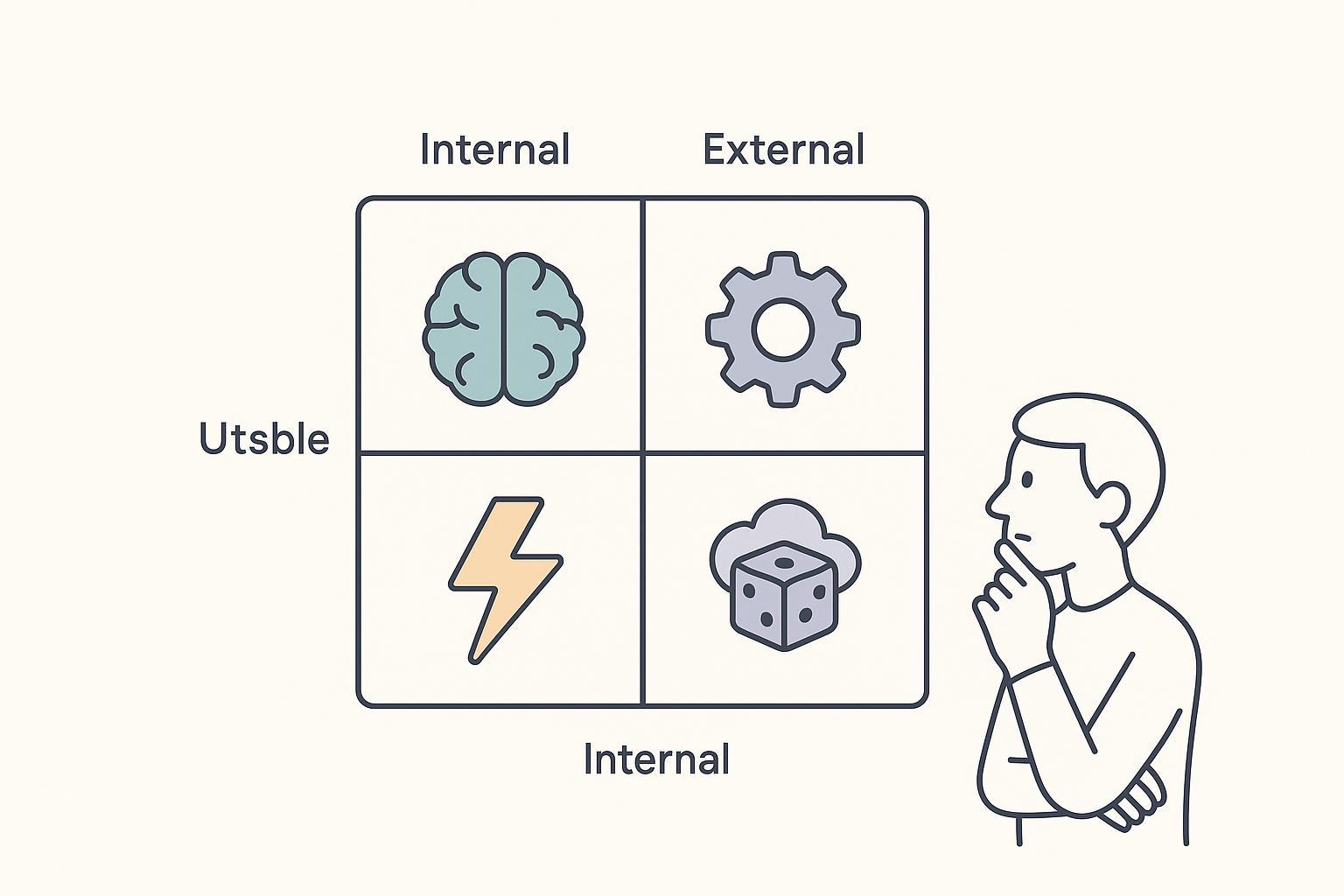

- The “four types” come from crossing two dimensions: locus (internal vs. external) and stability (stable vs. unstable).

- The four cells are internal–stable, internal–unstable, external–stable, and external–unstable; each leads to different expectations and feelings.

- Bernard Weiner’s model adds a third dimension—controllability—which helps explain emotions like pride, shame, pity, and anger and how they affect motivation.

- Common errors (like the fundamental attribution error) can skew our judgments about ourselves and others.

- Clearer attributions can improve feedback, learning, teamwork, and self-reflection.

The four types at a glance

Psychologists often teach the “four types” as a simple 2×2 grid. A reader-friendly mapping with classic examples appears in Simply Psychology’s attribution theory explainer.

| Locus → / Stability ↓ | Internal | External |

|---|---|---|

| Stable | Ability; enduring traits | Task difficulty; rules/policies |

| Unstable | Effort; strategy; mood | Luck; weather; one-off events |

Let’s bring each cell to life with everyday examples.

1) Internal–Stable: “It’s who I am” (ability or enduring traits)

- Exam: “I aced the calculus test because I’m good at math.”

- Sports: “She’s consistently fast because she’s a naturally gifted sprinter.”

- Work: “He closes deals easily because he has strong social intuition.”

Implication: Stable internal causes suggest similar outcomes will occur again, raising or lowering expectations accordingly. When we attribute failure to low, stable ability, it can reduce hope for improvement.

2) Internal–Unstable: “It’s what I did (this time)” (effort, strategy, mood)

- Sales: “I missed quota because I didn’t prepare my list well this month.”

- Study habits: “I crammed too late and slept poorly, so my focus slipped.”

- Teamwork: “We underdelivered because I chose the wrong approach; I’ll switch tactics next sprint.”

Implication: Unstable internal causes preserve agency and hope. If effort or strategy led to the outcome, you can adjust next time.

3) External–Stable: “The system is built that way” (task difficulty, rules, structures)

- Project: “Our release slipped because the approval workflow is rigid.”

- Education: “This course curves harshly; even strong students average a B.”

- Competition: “The market is dominated by a few incumbents with entrenched distribution.”

Implication: Stable external causes suggest persistent constraints unless the environment changes.

4) External–Unstable: “It was circumstantial” (luck, weather, disruptions)

- Marketing: “A rival launched an unexpected flash sale during our campaign week.”

- Logistics: “A surprise snowstorm delayed shipments.”

- Events: “A keynote cancellation shifted attendance patterns at the last minute.”

Implication: Unstable external causes imply variability. Results may differ next time even without changing your approach.

Beyond the 2×2: Weiner’s third dimension—controllability

Bernard Weiner’s influential model formalizes three dimensions—locus, stability, and controllability—and links them to emotions and motivation (see Weiner’s 1985 Psychological Review article). Britannica’s overview highlights how stability affects expectations and how controllability colors our emotional reactions.

Here’s how common causes map out:

- Ability: internal, often stable, generally uncontrollable in the short term.

- Effort: internal, unstable, typically controllable.

- Task difficulty: external, can be stable, typically uncontrollable for the individual.

- Luck: external, unstable, uncontrollable.

Why controllability matters

- Emotions: Success attributed to controllable internal causes (effort, strategy) tends to evoke pride; failure attributed to controllable causes can bring guilt and prompt corrective action. Failures tied to uncontrollable internal causes (e.g., perceived low ability) can lead to shame and resignation; uncontrollable external causes (bad luck) often soften self-blame. These patterns are core to Weiner’s model.

- Motivation and expectations: Stability informs whether we expect the same result next time, while controllability guides whether we try to change anything. For instance, attributing a poor presentation to fixable preparation (internal, controllable) primes concrete improvement; attributing it to immutable “lack of charisma” (internal, stable, uncontrollable) discourages effort.

Illustration: Suppose a student fails an exam. Four explanations and outcomes

- “I’m bad at science” (internal, stable, uncontrollable): lowered expectancy, discouragement.

- “I didn’t study effectively” (internal, unstable, controllable): constructive guilt, plan to adjust methods.

- “The test was unusually hard” (external, stable): recognition of systemic difficulty; may seek support or a different course.

- “I got unlucky with the questions” (external, unstable): emotions ease; try again with broader prep.

A 2025 Frontiers in Psychology study of online math learners reported that stronger control appraisals and effort beliefs predicted more positive achievement emotions and fewer negative ones, consistent with attribution theory’s emphasis on controllability and effort.

Common attribution pitfalls (and how to avoid them)

- Fundamental attribution error: We tend to overemphasize others’ internal traits and underplay situational forces. For instance, we might label a colleague “careless” rather than consider their overloaded queue. See the APA Dictionary entry on the fundamental attribution error.

- Self-serving bias: We often credit our successes to internal causes and blame failures on external ones. This bias can hinder learning after setbacks; brief self-audits (“What part was in my control?”) help counterbalance it. See APA’s definition of self-serving bias.

Simple guardrails

- Ask “What else could explain this?” to surface situational factors.

- Separate locus from controllability: An internal cause can still be changeable (effort, strategy).

- Frame feedback around controllable factors to support growth.

Quick boundary: Psychological vs. marketing attribution

The word “attribution” also appears in marketing analytics, but it refers to assigning conversion credit across ad touchpoints (e.g., first-click, last-click, linear, time decay, position-based, data-driven). For concise definitions of these models, see Google Analytics 4’s attribution models documentation. This is unrelated to psychological attribution theory, beyond sharing the term “attribution.”

Try it: Fast reflection prompts

- Think of your last success. Did you explain it by stable ability, effort, helpful conditions, or luck? How did that affect your next steps?

- Think of your last setback. Which elements were controllable? What small change could you test next time?

- In team debriefs, list at least one internal–unstable (controllable) and one external factor before deciding on action items.

Summary

- The “four types of attribution” come from crossing internal vs. external with stable vs. unstable causes.

- Weiner’s addition—controllability—explains why similar outcomes can generate very different emotions and motivations.

- Watching for biases and emphasizing controllable causes can improve learning, resilience, and collaboration.

Sources and further reading

- The definition of attribution and attribution theory in the APA Dictionary of Psychology provides authoritative grounding.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica’s overview of locus, stability, and controllability connects attributions to motivation.

- Simply Psychology offers an accessible mapping of ability, effort, task difficulty, and luck across the 2×2 grid.

- Bernard Weiner’s 1985 Psychological Review article lays out the three-dimensional model linking attributions to emotion and motivation.

- A Frontiers in Psychology study (2025) illustrates how control appraisals and effort beliefs relate to students’ emotions in online math learning.

- For the marketing analytics meaning of “attribution,” consult Google Analytics 4’s attribution models documentation.

References (linked above)

- APA Dictionary of Psychology: Attribution; Attribution theory; Fundamental attribution error; Self-serving bias

- Britannica: Motivation—attribution dimensions (locus, stability, controllability)

- Simply Psychology: Attribution Theory

- Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548–573

- Frontiers in Psychology (2025): Online mathematics learning emotions and control appraisals

- Google Analytics 4 Help Center: Attribution models