Brinson Attribution: What It Is, How It Works, and Why It Matters

Brinson attribution is a benchmark‑relative framework that explains a portfolio’s excess return by “slicing” it into the impact of three active decisions: how you weight groups versus the benchmark (allocation), how your securities perform within those groups (selection), and the residual cross‑term from doing both at once (interaction). In other words, it tells you whether your outperformance came from being in the right places, picking the right names, or both.

This explainer is written from the perspective of a performance analyst who produces attribution reports for clients and exam candidates. It focuses on equity/sector Brinson attribution—the most common use case—while noting boundaries and alternatives where appropriate.

Why Brinson attribution matters

Active managers are judged on the decisions they control. Brinson attribution connects excess return to those decisions in a way clients and investment committees can understand. A concise historical overview of attribution’s development and purpose is available in the CFA Institute Research Foundation’s 2019 “Performance Attribution” overview, which traces the evolution of return-based attribution and its role in manager evaluation.

The three effects, intuitively and formally

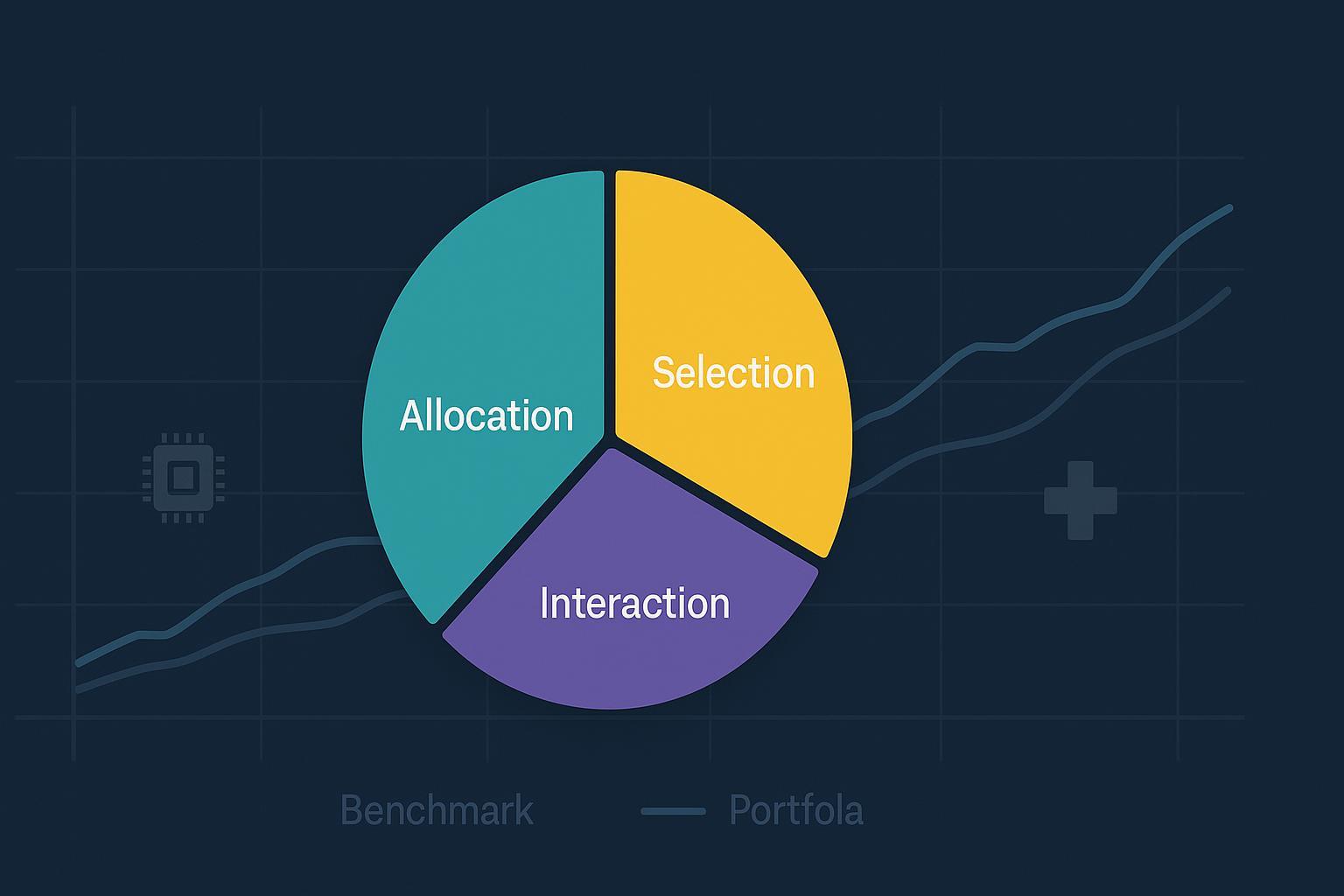

Think of excess return as a pie you can cut into three slices:

- Allocation: the effect of overweighting or underweighting groups (sectors, countries, asset classes) relative to the benchmark.

- Selection: the effect of your holdings performing better or worse than the benchmark’s constituents within each group.

- Interaction: the cross-term that occurs when you both change weights and achieve different relative performance in the same groups.

Compact formula panel (single period, arithmetic Brinson)

For group i:

- Allocation_i = (w_p,i − w_b,i) × R_b,i

- Selection_i = w_b,i × (R_p,i − R_b,i)

- Interaction_i = (w_p,i − w_b,i) × (R_p,i − R_b,i)

Sum over all groups: Excess return = Σ Allocation_i + Σ Selection_i + Σ Interaction_i.

These widely used expressions appear in practitioner methodologies such as Morningstar’s Equity Performance Attribution Methodology (2009/2011).

Variants: Brinson–Fachler vs Brinson–Hood–Beebower

Two names come up frequently:

- Brinson–Fachler (JPM, 1985): Emphasized sector-level, non‑U.S. equity attribution and presented formulas closely aligned to the arithmetic expressions above; the historical framing is summarized in the CFA Institute Research Foundation overview cited earlier (2019).

- Brinson–Hood–Beebower (FAJ, 1986; revisited 1991): Popularized decomposition across asset classes/sectors and the allocation/selection/interaction triad.

In practice, vendors may present slightly different sign conventions or reporting choices, but the core idea—decomposing excess return into allocation, selection, and interaction—remains the same.

Arithmetic vs geometric attribution and multi‑period linking

- Arithmetic attribution is additive and intuitive for a single period. However, single‑period excess returns generally do not add up to the multi‑period excess return because returns compound multiplicatively.

- Geometric attribution respects compounding by working with geometric excess return: G = (1 + R_p) / (1 + R_b) − 1. It is often preferred when you need multi‑period tie‑outs and cross‑currency consistency. Nuances around whether “interaction disappears” in geometric variants have been clarified—interaction can arise depending on the derivation. See Ortec Finance’s 2018 research note on geometric attribution and interaction.

If you report arithmetic single‑period effects across multiple periods, you need a linking method to reconcile their sum with the total excess return:

- GRAP/Menchero: An industry standard scaling formula that ensures additivity to the full-period excess return; see TSG Performance’s 2010 explainer on the GRAP attribution linking formula.

Linking introduces communication trade‑offs (period effects depend on later returns), so be transparent about the method used.

A small worked example (arithmetic Brinson–Fachler style)

Setup: Two sectors, Tech and Health.

- Benchmark weights: Tech 60%, Health 40%.

- Portfolio weights: Tech 70%, Health 30%.

- Returns in the period: Benchmark Tech +5%, Health −2%; Portfolio Tech +6%, Health −3%.

Compute effects per sector:

- Allocation: Tech (0.70−0.60)0.05 = +0.005; Health (0.30−0.40)(-0.02) = +0.002 → Allocation total = +0.007 (0.70%).

- Selection: Tech 0.60*(0.06−0.05) = +0.006; Health 0.40*((−0.03)−(−0.02)) = −0.004 → Selection total = +0.002 (0.20%).

- Interaction: Tech (0.10)(0.01) = +0.001; Health (−0.10)(−0.01) = +0.001 → Interaction total = +0.002 (0.20%).

Sum: Excess return = 0.007 + 0.002 + 0.002 = +0.011 (1.1%). This ties out for the single period, which is why arithmetic Brinson is easy to explain to clients. Comparable step‑throughs are presented in Morningstar’s methodology (2009/2011).

Data requirements and assumptions (the hygiene checklist)

Accurate attribution depends on clean inputs and consistent conventions:

- Grouping scheme: Use the same sector/country classification (e.g., GICS) for both portfolio and benchmark.

- Weights and timing: Align weights and returns in time (e.g., beginning‑of‑period or average weights) and handle corporate actions and trades carefully; see methods discussed in the Morningstar methodology (2009/2011).

- Benchmark integrity: Ensure the benchmark represents the investable universe relevant to the mandate.

- Gross vs net: Clarify whether attribution is done gross or net of fees, and ensure excess return aligns with that choice.

- Currency: For global portfolios, consider separating a currency effect or using geometric attribution to maintain compounding and translation consistency.

Standards-wise, the Global Investment Performance Standards do not mandate a specific attribution model. If you present attribution, you should disclose the methodology and assumptions to ensure fair representation. See the CFA Institute’s 2020 GIPS Standards for Firms.

Common pitfalls and interpretation tips

- Cash treatment: Decide whether cash is a separate segment. Inconsistent cash handling can inflate allocation effects.

- Reclassifications: Sector or industry reclassifications mid‑period can create spurious effects; fix mappings for the analysis window.

- Transaction timing: Misaligned weight timing (e.g., using end‑period weights) can distort allocation/selection attribution.

- Currency and compounding: In multi‑currency portfolios, geometric attribution often reduces residuals and improves tie‑outs.

- Interaction reporting: Some firms display interaction explicitly; others fold it into selection for client simplicity. For pros and cons of each approach, see FactSet’s 2016 “Equity attribution and the delicate art of interaction”.

Interpretation tip: Treat allocation and selection as diagnostics, not verdicts. A large selection effect in one sector may reflect concentrated bets, temporary dislocations, or benchmark construction quirks. Always triangulate with position‑level contribution, risk exposures, and mandate constraints.

Boundaries: what Brinson is—and isn’t

Brinson is a return‑based decomposition of benchmark‑relative performance. It is not:

- Risk attribution (e.g., explaining variance or tracking error contributions).

- Factor/style attribution (e.g., Fama–French exposures and their return premia).

- Fixed‑income yield curve or spread attribution (which requires different models).

When your objective is to explain performance via exposures to systematic factors or to diagnose risk drivers, a factor or risk‑based approach may be more appropriate. Brinson is most informative when evaluating active allocation and security‑selection decisions against a well‑chosen benchmark.

Practical takeaways for analysts and PMs

- Start with a clean, agreed‑upon classification and benchmark.

- State your conventions: weights timing, gross vs net, treatment of cash and currency.

- For single periods, arithmetic Brinson is simple and intuitive; for multi‑period reporting, prefer geometric attribution or apply an explicit linking method (e.g., GRAP) and disclose it.

- Use interaction deliberately: display it when it adds insight; otherwise explain how it is incorporated.

- Always pair attribution with contribution analysis and position context.

Educational disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes and general information only. It does not constitute investment advice, an offer, or a recommendation. Methodologies and examples are simplified to illustrate concepts; real‑world implementations should be tailored and fully disclosed per applicable standards and client agreements.

References and further reading

- Historical overview: CFA Institute Research Foundation – Performance Attribution (2019).

- Methodology and formulas: Morningstar – Equity Performance Attribution Methodology (2009/2011).

- Geometric attribution nuance: Ortec Finance – Geometric attribution and the interaction effect (2018).

- Multi‑period linking: TSG Performance – The GRAP attribution linking formula (2010).

- Standards and disclosure: CFA Institute – 2020 GIPS Standards for Firms (PDF).

- Reporting choices: FactSet – Equity attribution and the delicate art of interaction (2016).